From collecting dead mice as a child to getting a postdoc studying mouse teeth

When I was little – five? maybe six? – I told my mom I wanted a dead mouse collection. I had found a few around our large back yard (probably the cat’s fault), and they looked so cute and soft and furry, I figured I’d bring them home.

Fortunately, my mom was used to my strange ideas. She stalled for time.

“Where would you keep your collection?”

I said I’d keep the mice in a fish bowl so people could see how cute they were.

“I don’t think they’d stay cute in a fish bowl.”

I offered to throw them out when they weren’t cute anymore, but my poor mom put her foot down.

“Honey, I don’t think dead mice are something people collect.”

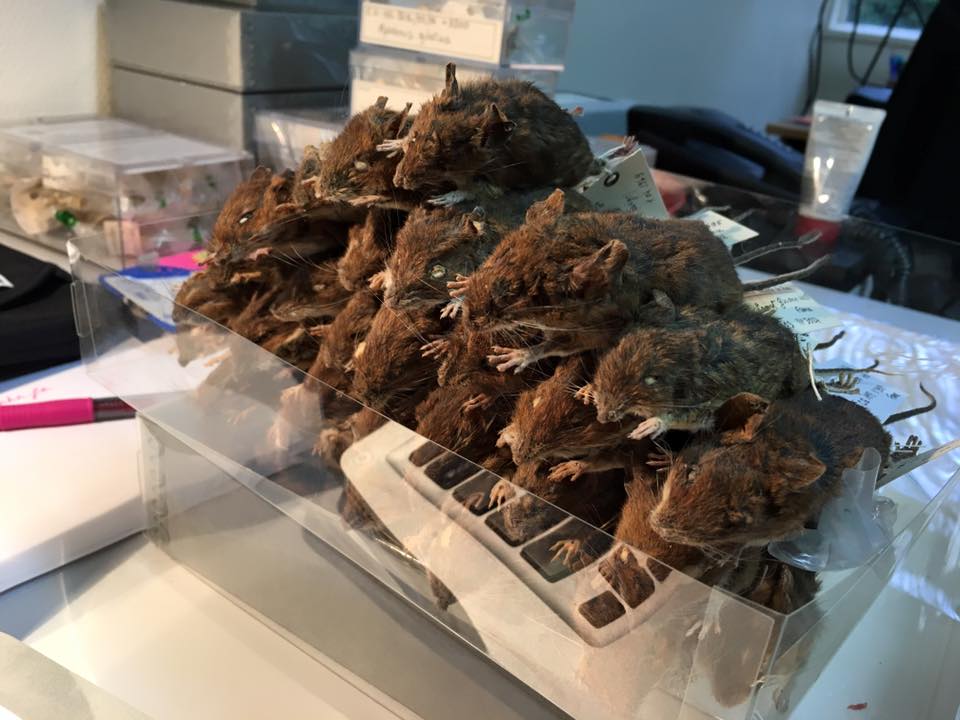

When I got my postdoc at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle studying mouse teeth, I sent my mom this photo:

Hell, yeah! They are!

My mom swears she doesn’t remember my aborted dead mouse collection, but I do – and props to my mom for constructive handling of my weird childhood enthusiasms. But what occurs to me most when I think about that story is the old plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: after fourteen years of higher education, I’m pretty much the same person I was when I was six.

I had another full circle moment yesterday. Back when I was fifteen, I attended the National Junior Classical League convention, which was being held at Indiana University Bloomington. While at the convention, I heard about the Lilly Library, IUB’s rare books, manuscripts, and special collections – and I learned that anyone – anyone! – could make an appointment to see the rare books. It blew my teenage mind! I could walk into this library and ask to hold a book that was hundreds of years old – and they would let me!

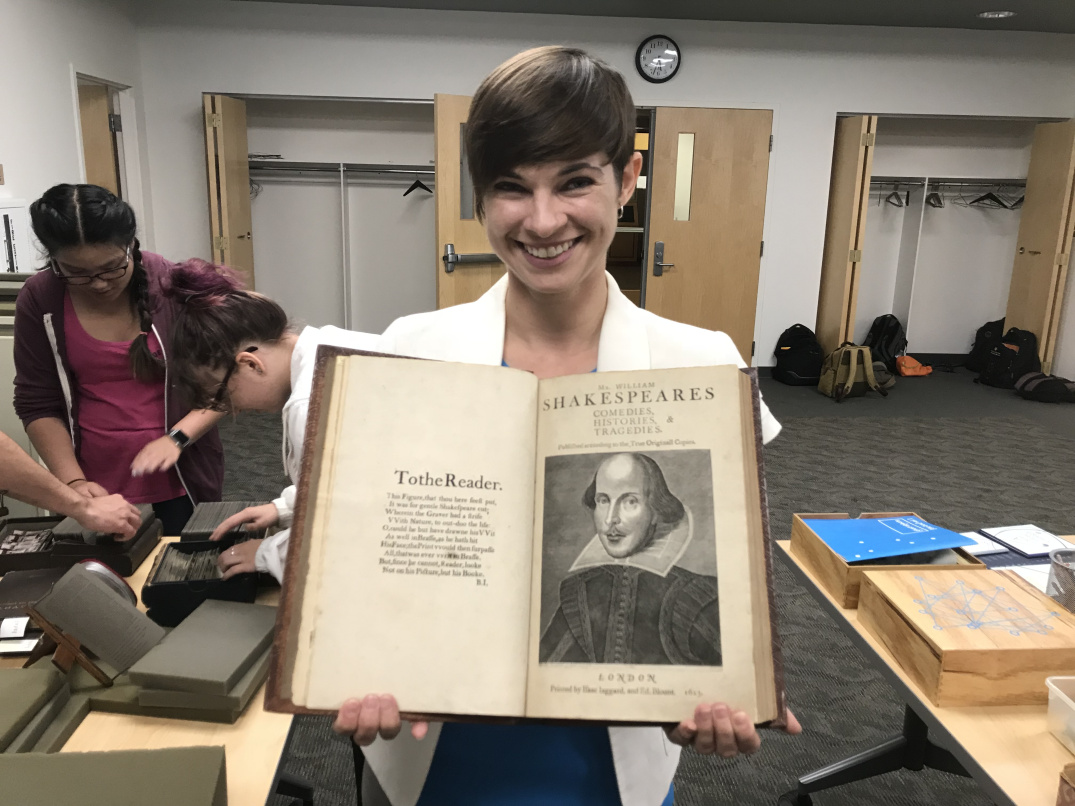

I put it to the test. Lo and behold, they sat me at a desk, set up props to hold the book, and brought me one of the first folios of Shakespeare, published in 1623. I remember hesitating to touch it, worried it would fragment, worried I would tear it if I turned a page. But the paper felt surprisingly resilient for a book over 350 years old, and I slowly gained confidence. For the next two hours, I sat in the quiet of the library reading Macbeth, my favorite play.

That first folio of Shakespeare was not the first artifact I had ever touched, but reading it in the Lilly Library was one of my first experiences entering the world of artifacts – that place where people valued and studied and worked to understand the past through its material remains. I had wanted to be an archaeologist since I was eight. Being treated like a researcher and trusted with a rare book made me feel like it was possible.

Yesterday, I took the students from my Discoveries of Archaeology course to the Walter Havighurst Special Collections of the King Library at Miami University of Ohio, where I am currently a Visiting Assistant Professor. Guided by the Head of Collections, William Modrow, my students handled dozens of objects: cuneiform tablets, medieval books of hours, Napoleon’s Description de l’Égypte, and late 19th century stereoscope images of archaeological sites to name a few. Cautious at first, as I had been, by the end of the visit they were picking up volumes and replacing them on their props, turning pages, switching out the stereoscope images, running their fingers over the tiny pressed symbols of the clay tablets. With plenty of time to explore, the students gravitated to what most interested them, and it seemed to be different for everyone.

I have no idea what particular interests drove each of my students, what their own personal curiosities and ideas and hopes might be. And I have no idea what the experience of the special collections will end up meaning to them. It may mean nothing particular, or end up just a curious memory, or be one of those cool ways college was broadening before they settle into something totally unrelated. For most, it probably won’t be formative. But we never know what experiences are going to matter to people. They may not know themselves until it’s twenty-two years later and they’re holding a first folio of Shakespeare.

Emily Holt (@Emily_M_Holt) is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Classics at Miami University. This story was published on October 5, 2018, on Emily’s blog, Errant (available here) and has been republished here with her permission.