My childhood love for nature sparked my research journey

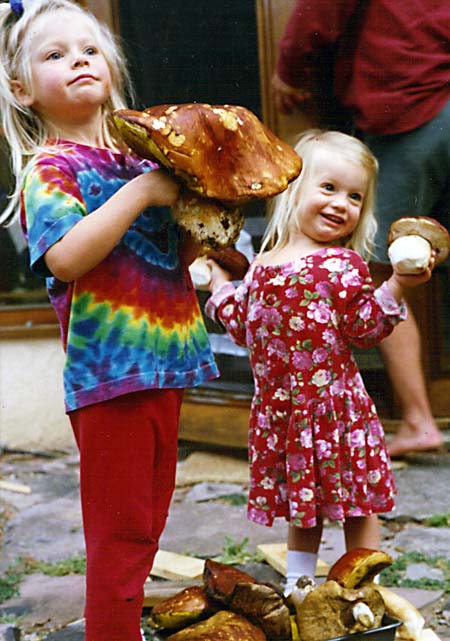

As a Pacific Northwest native and the daughter of a fungi-fanatic and hiking enthusiast, my childhood was filled with environmental education and global exploration. As a six-year-old, I enthusiastically and quite accurately named every Salal plant (Gaultheria shallon), Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium), and Monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana) that I saw. I loved spending time outside, learning about new plants and animals from my parents. However, my favorite activity was mushroom-hunting. Wandering through the evergreen forests of the Pacific Northwest, my family and I scoured the forest floor looking for bright orange chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius); this was my own personal treasure hunt. I not only loved finding the mushrooms but I was elated once I finally got to eat them.

Little girls, big boletes

Chanterelles bounty

My love for nature inspired me to apply for the Environmental and Adventure School, an alternative to public school in my district—which I must admit was quite serendipitous. At this school, much of our time was spent engaging in outdoor exploration, education, and community service. Here I learned more about the outdoors but also shared my knowledge with my peers. Then, at 13 I traveled to Venezuela with my family. As I hiked through the lush jungle, I was mesmerized by the magenta petals blanketing the forest floor and was excited by the cacophony of calls echoing through the jungle. The life-changing two months I spent backpacking through Venezuela and Peru inspired me to take a gap year after high school, after which South America was my first stop.

I was stunned by Latin America’s natural beauty. I fell in love with the verdant hills surrounding Rio de Janeiro teaming with wildlife. As I fed toucans, monkeys, pygmy marmosets, and porcupines under the guidance of a local park ranger, I realized this country was very special – not only were the people vivacious and colorful but the ecosystems hosted a suite of flora, fauna and fungi. However, as my travels continued I was deeply saddened to learn about the great duress that deforestation and development were exerting on all forests, particularly the Amazon rainforest. It was during this trip that I found my life’s calling: conservation.

Upon returning to the States, I was determined to protect the Amazon rainforest. I began my Bachelor’s studies and was fortunate to find a research assistantship focused on tropical forest conservation in Peru. The many projects I worked on opened my eyes to the world of conservation science. For my first project, I was tasked with translating and analyzing survey data from Peruvian farmers and gold miners. We sought to identify their interest in various forest conservation programs for which we would pay them to engage in non-extractive work. My work was challenging and exciting—plus I was learning so much!

Next, I was invited to travel to Peru to map and monitor selective illegal logging using an eco-drone. This project opened up a whole new side of conservation for me: fieldwork and failure. Using a drone is about as challenging as it sounds, if not more difficult. Despite our valiant efforts to learn the autopilot software and program our drone, it truly had a mind of its own. While we were unsuccessful in gathering the data we had hoped for, I learned that the key to success in science is perseverance. However, after two summers of struggling with a drone, watching it crash, and jerry-rigging it so we could try again, we conceded. Researching in the remote regions of the Amazon is not only physically challenging but also leaves you without both an internet connection to google potential solutions as well as phone communication to call in the experts. Despite the snags in our research attempts, I was still certain that I was on the right path.

Drone balancing

Upon returning to Seattle after another long summer of research, it was during my penultimate quarter at the University of Washington that my eyes were opened to conservation psychology. I had an epiphany—to engage the Peruvian farmers in conservation efforts, we needed to understand their behavioral antecedents, not just their hypothetical interest in conservation programs. Thus, I found a conservation psychology research assistantship working to engage students in sustainable behavior and in another project, working towards resolving stakeholder conflict surrounding the management of the Olympic Experimental State Forest. Analyzing and coding focus group transcripts was my first experience undertaking qualitative research and this experience opened my eyes to the power of words rather than numbers for solving conservation-related issues.

To merge my interests in conservation and the behavioral sciences, I pursued a bi-national Master’s degree in International Nature Conservation through Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (Germany) and Lincoln University (New Zealand). This is a unique international program where students spend the first two semesters at the respective host universities and thereafter get to choose the institutions they would like to study at for their third and fourth semester. Not only was this an incredible opportunity to see the world but it also allowed me unparalleled flexibility to pursue my interests in both tropical conservation and conservation psychology. I continued to hone my knowledge of tropical forest ecosystems through my coursework but was able to expand upon my conservation psychology research experience during my third and fourth semester.

For my third semester, I interned at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), as their first-ever conservation psychology intern. Here, I developed a practitioner’s handbook for designing and implementing behavior change interventions to support WWF practitioners in integrating the science of behavior change into their interventions. Subsequently, for my fourth semester, I worked for Dr. Carena van Riper, where I explored how people’s values influence their environmental behaviors in Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska. These opportunities solidified my desire to pursue a PhD in Conservation Psychology. Human behavior is integral to the success of conservation-related initiatives, yet it is largely ignored in conservation interventions. Being part of a burgeoning discipline is both exciting and challenging—one must create many of their own opportunities.

However, I would like to say that although my journey so far has been perhaps unconventional and definitely winding, my childhood love for nature was fundamental in guiding my career path. Each step of the way I found new and exciting aspects of the environment that modified the course of my journey. I have just finished applying to PhD programs and am eagerly awaiting responses. Despite my focus on nature conservation, most of my time is spent at my computer. Thus, between my Master’s and PhD I have taken a bridge year to spend time in Latin America, brush up on my Spanish and ultimately spend time outside in nature before beginning my PhD next fall where I will continue to research how behavior change science can be applied to tropical forest conservation efforts in Latin America.